Hydrocephalus

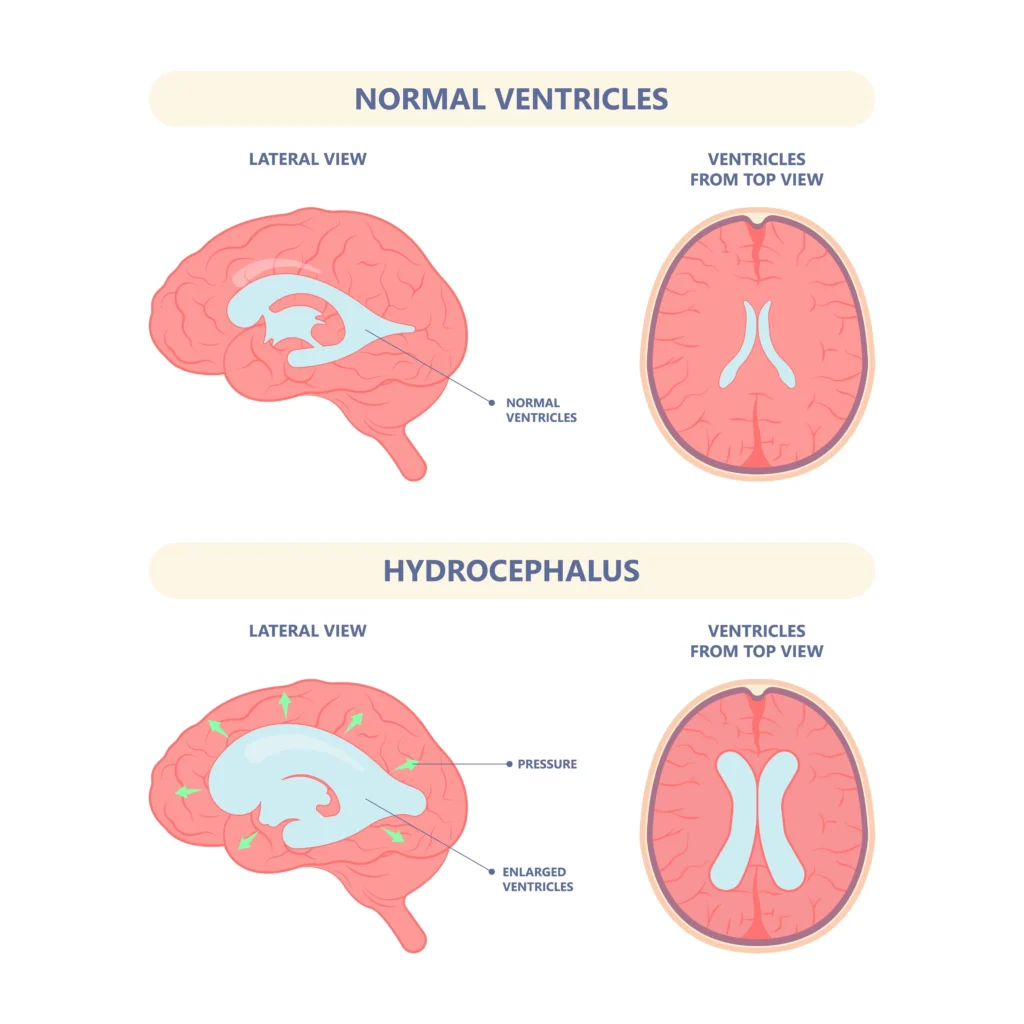

Hydrocephalus is an abnormal build-up of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the ventricles inside the brain. The ventricles are fluid-filled spaces in the brain. CSF is a clear, colourless fluid that looks like water and contains small amounts of salt, sugar, and cells.

CSF circulates in the ventricles inside the brain, to the outside of the brain, and around the spinal cord. If CSF flow becomes blocked, it builds up in the ventricles and presses against the brain. This is called hydrocephalus.

CSF is constantly produced in the ventricles. It moves around the brain and spinal cord, is absorbed, and is then replaced by new CSF. Some of the functions of CSF are:

- to protect the brain and spinal cord from injury

- to nourish brain cells, which helps with brain functioning

- to carry waste products from brain cells away

- CSF moves around the brain and spinal cord on a specific pathway. When too much CSF gets trapped anywhere along this pathway, it can expand the ventricles and put pressure on the brain. This condition is called hydrocephalus.

There are two types of hydrocephalus:

Communicating hydrocephalus is the build-up of pressure from too much CSF that is not being properly absorbed.

Non-communicating hydrocephalus is the build-up of pressure from CSF when a blockage occurs within the brain. Some causes of non-communicating hydrocephalus may be a tumour, a blood clot, or a narrowing of part of the CSF pathway found at birth.

A person born with hydrocephalus is said to have congenital hydrocephalus. Those who develop it later in life are said to have acquired hydrocephalus.

Signs of hydrocephalus

Your baby may have some or all of the following symptoms:

- poor feeding

- vomiting (throwing up)

- sleepy (hard to wake up) or not as awake or alert as usual

- large head (your family doctor can measure this)

- bulging soft spot (fontanelle) on the top of the head

- seeming irritable (cries easily or without reason)

- seizures

- very noticeable scalp veins

- slowness at reaching milestones (for example, slow to roll over, slow to sit)

- “sunset” eyes, when the eyes appear to be always looking down and are not able to look up

Hydrocephalus is often diagnosed with imaging tests

These tests include CT scan, MRI, and ultrasound. These technologies give doctors different views of what is going on inside the brain. These imaging tests may reveal a blockage or a build-up of CSF.

Hydrocephalus is treated with surgery

There are no effective medicines for hydrocephalus. Most children require surgery. The goal is to lessen the pressure in the brain by providing another pathway for CSF to be drained and absorbed away from the brain.

There are two types of surgery for hydrocephalus:

- The most common treatment is the insertion of a shunt. The shunt works by moving fluid from an area where there is too much CSF to an area where it can be absorbed into the body.

- Some children with non-communicating hydrocephalus can have surgery called an endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV). This surgery creates an opening to allow CSF to flow in and around the brain as it should.

Shunt surgery

The most common treatment of hydrocephalus is the surgical placement of a shunt. A shunt is a soft, flexible tube.

The top end of the shunt is placed in the ventricle fluid spaces inside the brain. This tube is attached to a valve that controls the flow of CSF through the shunt. The tube is then tunnelled below the skin to an area of the body where the fluid can be absorbed. One area is the lining of the abdominal cavity (the peritoneum). This is called a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt (VP shunt).

Shunt

A shunt is placed in one of the ventricles of the brain. It is threaded under the skin into the abdomen. The shunt drains cerebrospinal fluid into the abdomen where it is reabsorbed by the body.

Less often, the shunt is connected from the brain to other parts of the body:

A shunt from the brain to the lining around the lung (pleural space) inside the chest is called a ventriculo-pleural shunt.

A shunt from the brain to veins draining into the heart is called a ventriculo-atrial shunt.

There are different types of shunt tubes and valves

Your child’s neurosurgeon will decide what type of shunt tube is best for your child. All shunts will only allow CSF flow in one direction. Some shunts may also have a small bubble or “reservoir” near the top that the doctor can use to take samples of CSF for testing.

Sometimes a special type of shunt is needed where the pressure setting is adjustable. This is called a programmable shunt valve. This allows the surgeon to program the shunt to control how much CSF is draining. It is important to remember that the pressure setting of this shunt can be changed by a magnet. MRI scans use large magnets, so if your child needs an MRI you must make sure to tell the doctor first about the shunt. An X-ray may need to be taken after the MRI to make sure that the pressure setting has not been changed.

During the shunt operation

Your child is brought down to the operating room and goes to sleep under general anesthesia. Your child will not feel any pain during the opreation.

The area from the head to the abdomen (belly) is scrubbed with a special soap. The surgeon makes incisions (cuts) on the head and abdomen. The shunt tubing is tunnelled just below the skin. The ventricular (top) end of the shunt is passed through a small hole in the skull made by the surgeon and gently passed into the ventricle. The abdominal (bottom) end is passed through a small opening in the abdomen. The incisions are then closed using staples or stitches.

The operation takes between 1 and 2 hours.

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) surgery

An endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is the second type of surgery done on some children who have hydrocephalus. Your surgeon will tell you if this surgery is possible for your child.

During an ETV, the surgeon makes an opening in the floor of the ventricle at the base of the brain. The CSF is then no longer blocked inside the ventricle. Now it can flow in and around the brain as it should.

This means that the child will not need a shunt, but instead will rely on the opening made by the surgeon during surgery. It is still very important to watch your child for signs that the pressure is building up again, as it is possible that the ETV could fail or become blocked. If any signs come back, it is very important to call your surgeon right away so that your child can be checked.

During the ETV operation, your child is brought down to the operating room and is put asleep under general anesthesia. Your child will not feel any pain during the operation. An incision is made on the head. A special scope with a camera on it is passed into the ventricle. The surgeon uses the camera to see the part of the ventricle that needs to be opened up. Once the opening is made, the surgeon will be able to see if the CSF is now flowing outside of the ventricle.

If the surgeon is not able to safely do the ETV, a shunt will be inserted instead. The incisions are then closed using staples or stitches.

The operation takes between 1 and 2 hours.

Longer-term:

A child with hydrocephalus needs to see a doctor often to make sure the shunt or ETV is working properly and that the pressure does not begin to build up again. Several members of a team will help and guide you as your child grows and develops. You should encourage your child to become involved in this ongoing process.

Key points

Hydrocephalus is an abnormal build-up of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the ventricles inside the brain.

Hydrocephalus is treated with surgery (an operation) to put in a shunt or create an endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV).